- Home

- Rene S Perez II

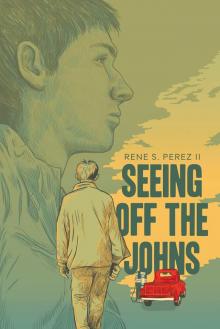

Seeing Off the Johns

Seeing Off the Johns Read online

Seeing Off The Johns. Copyright © 2015 Rene S. Perez II. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written consent from the publisher, except for brief quotations for reviews. For further information, write Cinco Puntos Press, 701 Texas, El Paso, TX 79901; or call 1-915-838-1625.

FIRST EDITION

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Perez, Rene S., 1984-

Seeing off the Johns / by Rene S. Perez II. — First edition.

pages cm

Summary: For Concepcion “Chon” Gonzales, the year that high school athletic stars John Robison and John Mijias left for college and never made it was the beginning of a new life in his small town and the first time he understood about love.

ISBN 978-1-941026-13-7 (EBook)

1.City and town life—Fiction. 2.Bildungsromans.I. Title.

PS3616.E74346S44 2015

813′.6—dc232014032016

BOOK COVER AND DESIGN BY ZEKE PEÑA

For Hammonds and Mejares, and for Natalie Rose

Contents

Before

Summer

Fall

Spring

2002

Acknowledgments

BEFORE

When word of the greatest tragedy in the history of Greenton made it back to town, the banner still floated over Main Street. “Hook ’em, Johns,” it read. It had burnt orange Texas Longhorns printed on both sides, the iconic symbol of the university the Johns were speeding toward—the symbol they were to wear on their ball caps come spring. There had been a police escort and the shutting down of Greenton’s businesses for a brief period so that its citizens could cheer on the young men all along the parade route—down through Main Street, under the banner, and out of town. After all, a Greentonite rarely made it to UT Austin, but for two of their own to enter its gates on baseball scholarships in one year warranted nothing less than a full-on celebration, a deep-seated compulsion to see off the Johns in style. They had graduated less than twenty-four hours before, walked across the stage set up at the Greenton High gymnasium, barely standing out from their classmates in their green caps and gowns. Now they were set to depart. By the end of the day, the Johns would be in Austin, unpacking in their new dorm, getting ready for summer classes and—most important—anticipating workouts the next day with their new coaches and teammates.

The fact that such a spectacle had been made of the Johns leaving town kept both the Robisons and the Mejias guarded and ill at ease in a time that should have been marked by unchecked emotions and copious nagging—“Are you sure you have the directions, have you checked the fluids in your car, the tire pressure?”

Arn Robison and his wife Angie left home in their Black Lincoln Town Car following John—their only child—as he made his way to John Mejia’s in his 1993 Ford Explorer, all of his possessions in the world filling up half of the truck. In the Mejia’s driveway, Robison got out and had a small conference with Mejia, one like the many they’d had throughout their high school careers: Mejia coming over to the mound from third base to give Robison his scouting report on a hitter from Falfurrias; Mejia behind the line of scrimmage stepping out from under center to turn and face his tailback Robison before returning to the business of calling his Huts and Mississippis and Blue 42s. Their in-game conferences were part of the legend of the Johns.

When they had their conference that morning—the morning of their leaving—presumably about how to put Mejia’s belongings in Robison’s truck—though it could have been about anything—people took photos. On-lookers exchanged stories and memories—their favorites from the Johns’ greatest hits—as though any of them had a game or play to talk about that hadn’t been witnessed by everyone else in town. The Johns broke their huddle of two quickly and set to loading the Explorer in under ten minutes—two large duffels, a trunk, a guitar, four plastic bags of non-perishables and four frozen meals in Tupperware that Mrs. Mejia made in the days leading up to the boys’ exodus.

When the car was packed, there were perfunctory hugs and kisses. Later the Robisons and Mejias would come to remember the spectacle of that day with bitter regret. They had allowed themselves to be caught up in the hype, had condoned the hero-worship of two young men who were not yet done being boys in Greenton’s frenzy and adulation. Under the prying gaze of their neighbors and peers, each boy had only allowed his parents a half hug and kiss before they got into the Explorer. They had, after all, reputations and images to maintain.

That day, the Mejias had to share their son with Araceli, the girlfriend he was leaving behind. She was still in high school, a senior. But they were used to sharing John with her. The kiss John Mejia gave Araceli, though, was as truncated and restrained as the affection he gave his parents. He leaned in close to whisper something to her, but she didn’t seem as keen as Robison to have her interactions with him play out in the form of whispers and nods. She pulled away and—very clearly to the audience’s eyes and ears—said, “Fine” and wiped her eyes.

The Johns got in Robison’s Explorer. Their parents flanked the truck, two Mejias at the passenger door and two Robisons at the driver’s. Tears were shed. Each parent leaned into the window that framed their son and, it seemed, tried to climb in to steal last minute hugs, egos be damned.

Then it was done. There was nothing more to say but goodbye. The parents stepped back from the truck in unison, like a space shuttle being shed of its rocket boosters. They stood on their respective sides of the Explorer, crying and beaming with pride and holding on to each other. Robison turned the engine.

The crowd outside the Mejia house fell silent. The police car waited expectantly at the curb. The Explorer pulled out of the drive and behind its escort. Robison stood on the brake so that he and Mejia could wave goodbye to their loved ones one more time. This having been done, the lead police car driver hit his siren. Everybody cheered, even the parents, having been pulled, half-heartedly, into the mob.

The police car took off, and the Johns followed. They got to the end of Sigrid, drove up Viggie to Main, and took that street out of town to the sounds of cheers and “The Eyes of Texas” blasted out over a P.A. system someone had set up for the forty seconds it took for the truck and its cargo of two to pass by, never to look back. But those forty seconds were worth it. No one could ever take those forty seconds away.

The crowds dispersed, talking of the season the Longhorns would surely have. Many were bold enough to forecast a trip to Rosenblatt Stadium in Omaha, a place some Horn fans called Disch-Falk North. Others were talking about their plans to go up to Austin to watch the Johns play at the park they themselves were already calling Greenton North. Finally they came back down to Earth, where there was work to be done and summers of mischief and sloth to be embarked on, smiling and with as much joy in their hearts as forty seconds can ever in a million years give to a whole town full of people.

SUMMER

Concepcion ‘Chon’ Gonzales didn’t partake of Greenton’s joy in those forty seconds. Instead he forced himself into eighty seconds of fake sleep interrupted by the sounds of sirens and the loud hootings of his neighbors and parents. Even his little brother Pito went out to cheer them on. The traitor. Chon pretended to sleep through the Johns’ parade to prove some point—a point he couldn’t quite define—to his family and to all of Greenton, but the town failed to notice his silent protest.

The night before, Pito made a big deal of asking their mother to wake him up early so that he could join in the morning festivities.

“Promise me, Mama,” he had begged, unnecessarily.

Chon’s parents wanted Pito to witness what could result from hard work

and skill, but they knew about Chon’s sulky dislike of John Mejia so they didn’t say much.

“Alright. Go to bed,” their mother said.

Pito clapped his hands excitedly and went to his room, avoiding his brother’s eyes. In the silence that followed, the rock chords of a beer commercial blaring from the TV underscored Chon’s anger at his brother and now at his parents. Chon sat at his end of the couch while his parents sat at the other, making a big deal of not mentioning the obvious—John Mejia’s spectacular success.

Chon spared them any further awkwardness by getting up, grumbling something about being tired after last night’s partying, and went to his room where he pretended to be asleep.

Chon hadn’t always cringed at the thought of the Johns, particularly at the thought of Mejia. His animosity was only four years old. It had existed for just under a quarter of his life and for the entirety of what he considered to be his manhood, from thirteen to that very day.

In elementary school, Chon had been the cutest and—that indicator of alpha male status—the tallest boy in his grade. Even then, it was clear to him that he could have for his girlfriend any girl he chose. Naturally, he chose the prettiest girl in school. From third grade through seventh, Chon Gonzales, the boy with the glowing hazelnut/amber brown eyes, had Araceli Monsevais at his side.

During this time, Chon played on Little League baseball and football teams alternately with and against the Johns. At many of these games, Araceli would sit in the stands and cheer Chon on. While she was there, more accurately, to cheer on her cousin Henry, who seemed always to be on any team Chon was on, Chon played every second in right field as though she were there for him and him only. He would make to run in the direction of any ball that was hit. In the event a ball was hit his way and he missed it, as he was likely to do, he would hustle to pick it up, try his damnedest to throw it where it needed to go, and pray that Araceli couldn’t see from the stands the tears that were burning in his eyes.

One of the lasting memories of Chon’s baseball days was the game when he had the good luck to smack a high curve—one the too-young pitcher he was facing shouldn’t have been throwing—with the sweet spot of his TPX, launching the ball into left-center field. After a sprint fueled by the desperation of a boy prematurely aware of the fleeting nature of Little League glory in a small town—a boy who knew that he wasn’t likely to ever hit a baseball that well again—and with the benefit of a throwing error from a left fielder who had fought with his center fielder teammate for the ball, Chon had enough time for a stand-up triple. He slid—Pete Rose-style—anyway. It was a great experience while it lasted. It should have made a great memory, except that when he got up and dusted himself off, he realized that Araceli hadn’t seen it. She had gone to get candy at the concession stand or to use the restroom or to do something that caused her to miss Chon’s only hit of the day—and the only extra-base hit of his short career.

That was the story of their relationship: poor timing and an inability to recreate a moment of glory.

That night, on the eve of the Johns’ departure from town, Chon lay awake thinking of possible ways in which he would win back the woman he felt destined to be his. Tomorrow Mejia would have the future and the rest of the world on the end of a string. With all of that good fortune coming to him, couldn’t he leave something behind?

John Mejia haunted Chon’s thoughts. But it was hard to extricate Greenton’s Romeo from its Juliet, if even only mentally—Chon couldn’t picture any version of Araceli without John Mejia at her side, at least any version he would want to focus on. The only John-less images he had of her were pre-John images.

The truth was, Chon could really remember hardly anything about his years with Araceli. How much attention did any boy pay to a girl before he is interested in sex? His interest in her was pure and fleeting, like so many other interests he picked up and put down when he was young. Sure they held hands, but only until their hands got sweaty. Sure they kissed, but what good is kissing when the kissers have no idea what it could lead to? They hadn’t even started talking on the phone in earnest teenage obsession.

And that’s all the Araceli that Chon could lay claim to: a pre-John one, an Araceli that Mejia seemed happy to concede to Chon, because he was never jealous. Mejia never registered Chon as a threat to his relationship with the most beautiful of Greenton’s daughters—not when he first took her from Chon, and not any time thereafter.

On the day he took her, a day at the beginning of seventh grade, Mejia made a big deal of waiting at Araceli’s locker to walk her to class. That was something Chon had done every now and then with Araceli, the girl he called his girlfriend, but who hadn’t called him her boyfriend in quite some time. While Araceli had achieved a firmness and amplitude of body in the summer between sixth and seventh grades, Chon, whose voice had not yet begun to break and squeak much less dip to the smooth baritone tenor of John Mejia’s, hadn’t seemed to notice. Once again, timing was off. Except that, this time, it was Araceli who hit for the fences and Chon who missed seeing it.

John Mejia didn’t miss it though. Chon never stood a chance against so much facial hair and muscles and bass and testosterone and so much burgeoning local celebrity. The Johns were already beginning their athletic takeover of the hearts and minds of Greenton. Strained as his relationship had become with Araceli, Chon wouldn’t have stood a chance against the opposition of any interested older boy. He didn’t fault Araceli for having snubbed him for one of Greenton’s two crowned princes. He simply figured, naively, that when his maturity and biology caught up to hers and to Mejia’s, he would win her back.

Time didn’t treat him so well though. He was plagued with such a case of acne that not even Christ would have touched him. He shot up in height from five nine to six four but couldn’t seem to gain an ounce of weight. Come eighth grade, he was a freak of nature and Araceli was dating the freshman starting quarterback and third baseman of Greenton’s most important varsity squads.

Chon lay in bed the morning of the Johns’ departure without a clue. How would he get Araceli back? His complexion was finally clearing. He’d managed to put on eight pounds during his junior year of high school. He no longer only saw ugly when he looked in the mirror. After some late night misadventures with Ana at work, he knew that he was walking around with hot blood in his veins and some experience to complement the desire that emanated from between his legs, controlling his every thought sometimes. But still Chon could only think of Araceli’s beauty in the context of her prom picture with Mejia.

So he slept uneasily, waking up from his light sleep when he heard Pito ask, “Did I miss it?” Their mother assured him that he hadn’t and shushed him up.

Chon could have just rested there quietly, staring at the ceiling or at the TV on mute or reading a magazine. Instead he forced his eyes shut and crammed his head between his pillows. Sleeping through the town’s final celebration of the Johns would harden Chon’s resolve to continue loathing a guy who never really did him wrong.

The first rush of applause, when the Robison family drove by his house en route to the Mejia’s, didn’t make Chon open his eyes. And he had fallen asleep for real by the time the sound of sirens and shouts passed by him some time later, waking him for the second it took him to realize what was going on. He closed his eyes in a calm and sinister fashion, like he imagined a super villain would. Because isn’t that what he was—Bizzaro trying to take Lois Lane from Superman?

When the day was over, he could tell himself he had slept through seeing off the Johns. He would emerge from his bomb shelter, guns in both hands, ready to fight the Nazis or the Russians or the Iraqis. He would right the wrong that had never really been done to him in the first place.

For good measure, and to put some distance between himself and his own stand—because what kind of stand would it have been if he’d backed down straightaway after not having made his point—Chon didn’t leave his room or get out of bed until three pm, thirty minutes befor

e he had to go into work. He slammed the door to his room behind him and took the quickest of showers, brushed his teeth, slapped on some deodorant, combed his hair, then hopped in his car, an ’89 Dodge Dynasty that had been dubbed the Dodge-nasty by Chon’s best friend in town and, thus, the known world, Henry Monsevais. Henry was also Chon’s old Little League teammate and perennial bottom-of-the-order brother. And he was Araceli’s cousin, younger by two weeks. Henry had taken the liberty of severing the cursive connection between the y and the n and scraping off the first two letters of the logo on the trunk of Chon’s car. When Chon saw what Henry had done, he laughed and said, “It fits.”

When, for the remainder of his sophomore year, everyone in school had taken to calling Chon “Dodge-nasty,” he was less than pleased.

“I’m sorry, man. If I had known—” Henry apologized when John Robison said, “Later, Dodge-nasty” out the window of his Explorer as he cruised by. Chon cut Henry off.

“Don’t worry about it,” he said. He was at the pinnacle of teenage self-loathing. “It fits.”

Everything looked normal on the way to work. There weren’t any more or less cars on the road. The driver of every car loosened his grip on his steering wheel to pick up the index finger and pinky of his two o’clock hand in the form of a wave. There were more kids in the yards he drove by—playing football or hide and seek or whatever kids play—but today was the first Saturday of the summer, so that was to be expected.

When he pulled onto Main, he saw the “Hook ’em, Johns” banner bobbing up and down, lazing in its perch over town. It was almost enough to make Chon cringe except that the Longhorn symbols on either side of the banner reminded him that the Johns were moving away, on to bigger and better. They would meet new friends, new girls—women even—in Austin. Greenton, Texas and Araceli Monsevais and that microcosm of relevance—that blip that didn’t even register on Mejia’s radar—Chon ‘Dodge-nasty’ Gonzales were to be forgotten. They would be written off as a part of the quaint past.

Seeing Off the Johns

Seeing Off the Johns